By Josh McGhee · DNAinfo Reporter

UPTOWN — Laura and her husband Jose have been “hop, skipping and jumping around” the North Side since they lost their home about three years ago.

Most recently, they’ve called the Wilson Avenue viaduct home, but before that they had a quaint apartment with a garden out back next to their patio and two-car garage.

The house had a big steel gate out front to help them feel safe from the streets of Chicago, says Laura, 51, who can remember the details vividly from her wheelchair parked a few feet from her “Personal Portable Possessions,” the small collection items she’s allowed to keep while living on the streets, according to a new city policy.

But tragedy struck the couple. Jose lost his job. The bank foreclosed on the house they were renting in. Her grandmother became ill and needed someone to take care of her. There was a car accident, which led to back surgery, she said.

“I’m disabled I’ll never be able to work again,” Laura said Tuesday. “These are people who lost their job or are disabled… and some are waiting for affordable housing. Not everybody that’s homeless is a drug addict or a prostitute.”

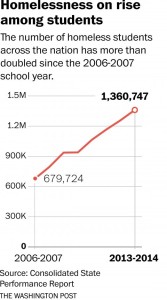

Homelessness on the Rise

In January, the Department of Family Support Services conducted its annual point-in-time survey and discovered the homeless population in Chicago had risen by roughly 8 percent.

About 6,786 people are homeless in Chicago and about 2,055 are unsheltered. About 68 percent of the homeless population is male, 32 percent is female and about .3 percent identify as transgender, according to the survey. The data is gathered by staff and volunteers who speak to homeless people they find on the street, and combines that data with numbers from area homeless shelters.

According to the point-in-time survey, about 57 percent of the sheltered were men, compared to about 43 percent of women. Those numbers have held steady since about 2009.

But when it comes to the unsheltered, those numbers jump to about 87 percent men, a five percent jump in the last year, according to the survey.

“There’s no place for men. There’s never going to be enough room. We’ll have space for single women. There’s just not enough room for men,” said Sandy Ramsey, the Executive Director of Cornerstone Community Outreach, at 4628 N. Clifton Ave. in Uptown.

Cornerstone has a capacity of about 80 men and 65 women. The men’s side, which is housed at Epworth United Methodist Church at 5253 N. Kenmore Ave, is almost always filled. Beds free up only for a fleeting moment, Ramsey said.

So where should those in need turn?

According to Ramsey: “There are no easy answers.”

A Crackdown in Uptown

In Uptown, homelessness is an issue that can not be ignored, partially because of visibility. The viaducts along Lake Shore Drive have long been home to folks with nowhere else to go. Laura and Jose called the Wilson Avenue viaduct home until Sunday, when police cleared about a dozen homeless people — mostly men — from the viaduct.

Around 5:20 p.m., officers told those under the Wilson viaduct they needed to pack up their tents and leave. Jose was one of those ticketed for using a “tent without permit,” which he plans to fight in court, he said.

After hearing about the incident, activist Andy Thayer came down to the viaducts seeking an explanation. When police returned around 8 p.m., they cited two different municipal codes they were enforcing. Activists claim the officers and others are misinterpreting the law “to drive out the homeless.”

“It’s just disgusting. [They’re] burdening more things on [people in] a bad situation,” said Thayer, a member of the Gay Liberation Network. “CPD has launched a coordinated attack on people who have nowhere to go.”

A Chicago Police spokesman had no information about the incident. A spokeswoman for Ald. James Cappleman (46th) said she was looking into it.

In similar case about two weeks ago, officers cleared homeless people from the Lawrence Avenue viaduct and gave them a set of rules detailing what “Personal Portable Possessions” they could carry. Activists say many of those homeless people ended up in a camping just west of the viaduct.

Confrontation Caught on Tape

In a video shot on Sunday by activists during a recent police effort to clear the viaduct, police cited Chicago Code 10-36-185, which allows police the authority to enforce provisions of the Chicago Park District Code.

Officers have also historically cited Municipal Code 10-40-560, which discusses congregations on bridges and viaducts.

The code states that it is “unlawful for any person to form or cause an accumulation of persons, animals or vehicles on any public bridge or viaduct, to any extent which may jeopardize the safety of such bridge or viaduct. No person shall persist in causing such accumulation, after being warned by a bridge tender, police officer or other person having supervision of such bridge or viaduct.”

During a recent protest called “Tent City” where activists spent a night with the homeless around the viaduct, Thayer says officers cited the same ordinances, but left after he explained the protest wasn’t taking place on Park District property.

“[The ordinance] was clearly designed for safety reasons, like parking a bunch of trucks under the bridge,” Thayer said. “This is the height of stupidity. [They’re] unconstitutionally driving homeless out of the ward to make it safe for gentrifiers.”

Patricia Nix-Hodes, director of the Law Project for the Chicago Coalition for the Homeless, said “neither ordinance seems appropriate for charging people at the Wilson Viaduct.”

“One relates to Chicago Police enforcement of park district ordinances and the other relates to Chicago harbors, and in any case only applies where the safety of a bridge or viaduct is jeopardized,” Nix-Hodes said. The Coalition for the Homeless has said the combination of information being distributed by different agencies has made the situation confusing for the homeless.

In a statement, Matt Smith, a spokesman for the Chicago Department of Family and Support Services, said the city “is committed to a compassionate and consistent approach to providing homeless services to ensure public safety while respecting the rights of this vulnerable population.”

“In addition to the ongoing outreach efforts to offer shelter and social services to homeless individuals on a daily basis, the City houses more than 3,000 people on any given night via our citywide network of overnight shelters and interim housing. We remain engaged in an ongoing dialogue with all stakeholders about how to best address the special needs and challenges of our homeless residents, and to assist every Chicagoan in having a place to call home.”

Nowhere To Go

After leaving the viaduct, the homeless weren’t given any directions about where to go, so they went into the park because “where else will they go,” Thayer said.

While temperatures Sunday afternoon were in the low 60s, they dropped to about 43 degrees around 1 a.m., forcing some to use their maximum allotment of “up to 10 blankets” to battle the elements.

Laura and Jose used their two shopping carts and chair to block the wind, a tarp “so we can be comfortable” and five blankets a piece to trap in the heat, they said.

“They didn’t tell us where to go and they didn’t care. We’re freezing, they don’t care. The temps drop at night and it gets really cold out here,” Laura said.

The battle over the viaducts has raged on since the homeless were cleared out in June ahead of a Mumford and Sons concert at Montrose Beach that was expected to bring large crowds. Cornerstone ended up sheltering about 20 people “because they are human beings in need,” Ramsey said.

“Rather than get into [if it’s legal or illegal to move them from the viaducts] I wanted to be practical. We just answered the call,” said Ramsey, adding most lasted about 5-6 weeks before returning to the viaduct.

“I think I understand, unfortunately, why they are under the bridge. There’s a certain amount of community that is down there.”

Cornerstone has sheltered many from the viaducts, but they don’t often stay long. Some people leave on their own and others “are asked to leave” when they can’t get along with other residents, Ramsey said.

It’s hard to for some to buy into the structures and guidelines, plus people “need space and air,” said Ramsey adding that most are welcomed back.

It’s also hard to show them the light at the end of the tunnel, considering it “takes about 40 days to get public aid” and those walking into Cornerstone are already on their last leg, she said.

“The long term thing takes a long time, and it takes a long time to maneuver a human being. Most of our people come in with no money. You’re trying to fashion a future out of nothing.”

RELATED STORY: Chicago Homeless Rules: 4 Shoes, 2 Coats, 5 Blankets