Even the most optimistic advocates know it’s a complex, costly concern

By Deborah L. Shelton

A little more than a decade ago, Chicago’s strategy for fighting homelessness mainly involved stopgap measures like pointing people to a temporary bed in a shelter and giving directions to a soup kitchen.

But then city officials, with the help of advocates, set about to better understand the needs of Chicago’s homeless population and offer services aimed at putting a permanent roof over their heads.

As a result, they say, the number of homeless people has not spiked despite a harsh economic recession. And now, as officials and advocates embark on a new seven-year plan to fight homelessness, they say they have a good shot at ending the problem altogether.

“We strongly believe that homelessness can be eliminated,” said Nonie Brennan, chief executive officer of the Chicago Alliance to End Homelessness, “and we believe that we can be the first major city in the nation to do it, and do it well.”

Even the most optimistic acknowledge that it won’t be easy, given the complexity of the issue. Not all homeless people have the same needs.

It won’t be cheap, either; the city Department of Family and Support Services plans to spend almost $48 million on homelessness in 2013 alone. And the sluggish economy is a persistent worry.

Yet city officials say they can do it by marshaling a variety of strategies. For example, a struggling family about to lose an apartment might get help paying the rent. That’s cheaper than trying to help after they are homeless.

Officials want to assist more homeless young people so they don’t become the next generation of homeless adults and help homeless people find jobs so they can better afford stable housing.

The city is providing subsidies directly to landlords who agree to rent to people who are homeless and helping to fund development of low-income housing for the homeless, such as single-room occupancy buildings.

The most potentially controversial part of the plan involves finding housing for people with problems like alcoholism and drug addiction who might never be able to pay for it on their own.

Such help represents a major change in thinking, but advocates say the approach stands the best chance at moving the most hard-core homeless people off the streets — those who have been living for years under bridges and in other public places.

Alexandria Banks, who has been homeless for 21 years and has battled addiction throughout her adulthood, realizes some people might see her as a lost cause. But Banks says she wants to contribute to society.

“Me, myself, I cannot come up with enough money for deposits and rent for an apartment; I need help. I desperately need housing,” said Banks, 51, who earns money selling StreetWise newspapers and doing odd jobs at a Hyde Park taco restaurant. “I am willing to do whatever I have to do to get it (housing), work whatever program, work community service — whatever I have to do.”

Not everyone agrees that the city’s effort, however laudable, can end homelessness. 49th Ward Republican committeeman Suzanne Devane called the plan “more PR spin than an achievable goal.”

The services being offered don’t get to the root causes of homelessness, and not all of those problems can be fixed by government intervention, Devane said.

“Many adult homeless have substance abuse and mental health problems. It is questionable whether much can be done in the way of intervention that will enable these folks to be contributing members of society,” Devane said in a statement. “There needs to be some type of supportive housing available to those willing to use it. Many won’t.”

Population count

In 2002, Chicago was one of the first cities to sign on to a 10-year national plan aimed at ending homelessness.

The plan focused on three main strategies: preventing homelessness whenever possible, placing people who lost their homes back into housing quickly and providing services to help them become self-sufficient.

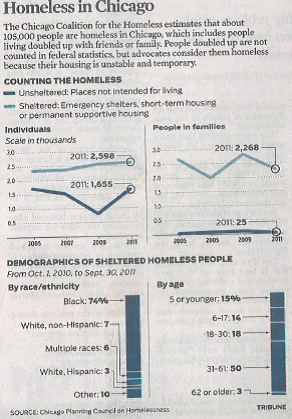

From 2005 to 2007, the number of homeless people declined, according to a “point in time” census the city conducts every other year during the last two weeks of January.

The count started to climb in 2009, but the 6,546 homeless people found in shelters and public places on a single night in January 2011 was still lower than the 2005 figure. This year’s census is still being analyzed.

Last year, as officials launched a new plan, they were encouraged in their efforts by success stories of people who have benefited from the new way of doing things.

Ashley Tutson, 26, had no place to live when she returned to Chicago from Memphis in 2010 with four children, but the idea of moving her young family into a short-term shelter terrified her. She came to the city to leave what she described as a volatile relationship.

“I already had the stereotype of shelters in my head — a huge room with a lot of beds and strangers coming in and out,” she said.

Instead she was referred to Madonna House, a shelter run by Catholic Charities of the Archdiocese of Chicago that opened in 2009. Instead of basic cots, she and her children were led to a private area with their own bathroom.

“The sense of relief that day was ridiculous,” Tutson said. “All of my kids had a bed. I can’t tell you when all of them had their own bed before that. We sat in the room and looked at each other and smiled. We were safe and we were OK and we were somewhere that felt like home. It was life-changing.”

The family later transferred to Catholic Charities’ New Hope Apartments program, which provided Tutson rental assistance, job counseling and other services.

Tutson completed training as a patient care technologist and phlebotomist and saved enough money from working a temporary job to cover a couple of months of rent. Although she is still looking for permanent employment, Tutson said she is far better off than if she had stayed in a shelter for a few weeks and then been shown the door.

What comes first?

Despite the image of a homeless person as a single man who suffers from substance abuse or mental illness, the reality is more complex. About 25 percent of the homeless have serious mental illness and 38 percent have a substance abuse problem, said Julie Dworkin, director of policy for the Chicago Coalition for the Homeless.

Some people have been pushed into homelessness after fleeing domestic abuse. Others have lost their jobs. Some are veterans. Many are working but earn too little to afford an apartment. There are families with young children as well as teenagers and young adults.

What they share is extreme poverty, Dworkin said. Chicago rents have skyrocketed since the 1980s, and it’s not uncommon for low-wage workers to spend most of their income on housing. “Any kind of small crisis can get them behind,” she said.

As officials and advocates developed their 10-year plan in 2002, they realized that some people would not become stable without receiving “wraparound” services such as education counseling, job training or treatment for addiction or mental illness. But they felt that those who were homeless needed a roof over their heads first.

Previously, the view had been that homeless people needed to solve their personal problems before they could expect help. But that approach didn’t seem to work, and officials concluded that it was unrealistic to expect someone to get sober while living under a bridge, to cite one example.

City officials redistributed resources to put more money into homelessness prevention and rental assistance programs. They also almost doubled the stock of permanent supportive housing, where wraparound services are provided. In November, a central referral system was launched that ranks individuals and families seeking such housing by their level of vulnerability and time spent homeless.

Maura McCauley, director of homeless prevention, policy and planning at the Chicago Department of Family and Support Services, said officials are “using our resources in a way that gets them to the people who need them the most.” Prevention at a price

Serving up a menu of services to get people back on their feet comes with a big price tag. Family and Support Services budgeted almost $48 million for homeless services in 2013, up from about $43 million the previous year, according to spokesman Matt Smith.

But not everybody needs intensive services. Some just need an apartment they can afford or help with rent for a couple of months to get them over a rough patch. Advocates say preventing such people from becoming homeless in the first place saves money in the long term.

“It’s much more expensive for society to have people homeless and cycling through emergency rooms and the criminal system, etc., than to devote resources to get them on their feet,” said Ken Keibler, department director for New Hope Apartments.

“People given the right support can succeed,” said Kathy Donahue, Catholic Charities’ senior vice president of program development.

Yolanda Fields, chief program officer of adult services at Breakthrough Urban Ministries, said helping people get jobs that pay a livable wage will be key to ending homelessness.

“We had 105 people who (recently) completed our job readiness program and 50 were placed in employment,” Fields said. “But the problem is, of the 50 who were placed, less than 10 percent were making over $10 an hour. They’re being employed as home health workers, security work, janitorial work — occupations that don’t pay a lot.”

Dworkin said employment services remain a shortcoming. “Our first 10-year plan didn’t have a focus on employment, so I don’t think we have a really good array of services,” she said.

Another problem is that the state and city are reacting to budget pressures by cutting back social service programs for people who could be at risk of homelessness, such as the mentally ill.

“It’s something we struggle with a great deal,” said Brennan of the Chicago Alliance to End Homelessness. “For every housing program we can bring on line, we need our sister agencies and the other programs that make up the social safety net to be in place.”

Although the city has been trying to move homeless people into permanent housing, there still have to be enough shelter beds for those who need them, said Jim LoBianco, executive director of StreetWise Inc., a local social service organization serving the homeless.

“One of the biggest challenges is the number of nonprofit groups that offer shelter beds that are closing their doors,” said LoBianco, who was deputy commissioner in charge of homeless services under former Mayor Richard M. Daley.

Dworkin said the new plan includes specific targets that allow planners to measure outcomes and keep the plan on track. But if the city cannot follow through for lack of money, the effort could fall apart.

Although the city’s plan has achieved some success, not enough permanent housing has been created, she said. An evaluation of the plan, she noted, found that a large number of people were still stuck in the shelter system.

“We need a lot more housing to be successful,” Dworkin said.

Despite the challenges, Chicago is well ahead of most cities in ending homelessness, said Philip Mangano, former executive director of the U.S. Interagency Council on Homelessness, an independent agency within the federal executive branch.

Chicago “ranks in the top tier,” said Mangano, who now heads the American Round Table to Abolish Homelessness, based in Boston. “I applaud Chicago for moving forward.”