Kellia Phillips is pictured with four of her children: Journee, 7 months, Jaleece, 15, Janae, 13, and Johnnie, 6. (Photo by Keith Freeman/Chicago Coalition for the Homeless)

Illinois’ child poverty rate is just as high as it was in 2010. Is the state doing enough to bring it down?

Kellia Phillips’ teen-aged daughters Jaleece and Janae run track. They have had to do so in ill-fitting shoes sometimes as old as three years.

Janae, 13, loves to knit and crochet. Her mother, says, “I could only get her yarn like every three months and she was so much into knitting and crocheting. I still can’t do that for her right now because I have no income.’’

Janae and her siblings would like bikes and a television, but that’s not in the picture any time soon.

“It’s very difficult right now, and I’m trying to pull it together so they can have the stuff they require and actually need,’’ says Phillips, who spent 4.5 years in shelters in Chicago with her children and now lives in Bronzeville on the city’s south side.

Phillips’ family, which includes six children between the ages of 7 months and 18, is a living example of the child poverty problem in Illinois.

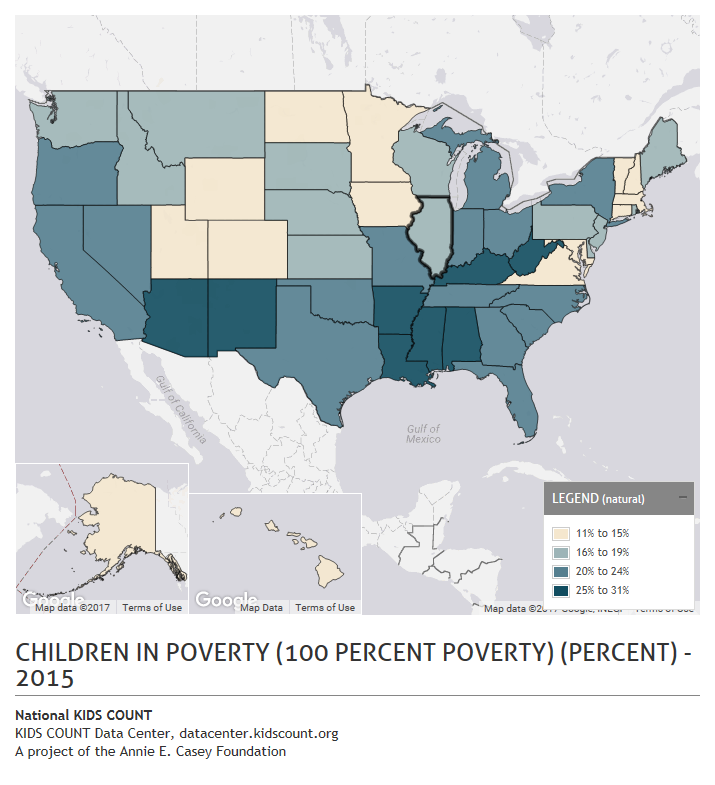

The Annie E. Casey Foundation annually compiles a national report with statistics on child well-being. In terms of economic well-being — defined as areas where factors such as the child-poverty rate and children whose families lack secure employment were measured —Illinois ranked 25th.

Anna Rowan, Kids Count project manager for Voices for Illinois Children, says, “Areas where we do well: We have a low rate of uninsured and a high percentage of children in early childhood programs. Where we don’t do so well are the indicators of economic well-being, specifically in our high poverty rate. We have 19 percent of our kids in the whole state who are living in poverty. That’s over half a million of our state’s kids. We need to focus on getting them and their families out of poverty.

“And the alarming thing is that this number hasn’t really changed since 2010, which was the height of the great recession, and our data only go up to 2015, so it’s important to know that we haven’t seen any possible impact of the state’s budget crisis on our numbers.”

What organizations working to assist the poor know is the mission has been harder in the face of a budget crisis. Though a Fiscal Year 2018 budget was approved in July, agencies are still waiting for money. As of Tuesday, there was a bill backlog of $14.5 billion, and $6.1 billion of those bills had yet to be sent to the comptroller’s office. A recent report by the Chicago Foundation for Women detailed some of the consequences of the impasse on organizations that help women and children.

“When this continued for a second year, were started to see a falloff in the number of women and children being served,’’ says K. Sujata, who is president and CEO of the foundation. “When we started talking to the organizations, we started hearing about layoffs and waiting lists and burnout. Certainly, in terms of our own anecdotal sense …we are seeing that people are not receiving services.’’

Mitch Lifson, senior policy analyst for Voices and a contributor to the report, says, “When you look at the demographics of those who are in poverty and what happened as a result of this budget impasse with the curtailment of cutback of services, it had a disproportional impact on women and children of color, and that, of course, makes the circumstances that they’re in more difficult for just getting by on a daily basis.”

But Meghan Power, director of communications for the Illinois Department of Human Services, counters, “Throughout the budget impasse, IDHS worked hard to maintain many programs that served Illinois’ children and families, including the Early Intervention program, the Women, Infants, and Children food assistance program, Family Case Management services, and our Child Care Assistance Program. … IDHS is continuously evaluating our programs in order to create systems that are effective and also sustainable in these hard times.

And Jason Schaumburg, director of agency communications for Gov. Bruce Rauner, wrote in an email:

“Since taking office, the Governor has worked on many initiates to address the needs of children and their families who are living in under-resourced communities.”

Among the initiatives directly related to poverty cited by the Rauner administration:

“Last year, the governor signed into law a bill that expanded the school breakfast program to an additional 175,000 children. Senate Bill 2393 made breakfast an official part of the school day for low-income schools in Illinois. It guarantees that every student has access to the healthy food they need to learn.”

Like hunger, there are real consequences for the children who are in need of services to help mitigate the effects of poverty.

Children living in poverty face greater chances of suffering from malnutrition, exposure to violence and other trauma and see limited educational opportunities as compared to kids who don’t have to deal with being poor, says Katie Buitrago, who is director of research at Heartland Alliance’s Social IMPACT Research Center. The alliance is an organization with initiatives that include anti-poverty programs.

Cristina Pacione-Zayas is director of policy at the Erikson Institute, a Chicago graduate school that focuses on child development and provides services to families.

“One area where poverty absolutely has an impact on how a child gets the resources and services they need that can either enhance their development or continue to depress their development. Another area to think about is their access to high quality early childhood education,’’ she says. “A lot of that is dependent on where your family lives: how easy it is to enroll in a program and if there are available slots, and, ultimately, if the program matches the schedule that this family needs for this child. We do know in research that early high quality education and care absolutely helps to mitigate the circumstances around poverty and the conditions of poverty.”

What are some of the effects of lack of school readiness?

“It has everything to do with is the child ready to be in a formal setting, and what I mean by that is does the child socialize well with his/her peers? Does the child follow instructions? Does the child know how to focus and attend to an activity or is the child going to be distracted and then do what it wants to do?” Pacione-Zayas asks.

“Children who are not ready for school can be labeled as having behavioral issues and then potentially get integrated into a special education program when actually it had nothing to do with what the child’s development but everything to do with was the child was prepared for and exposed to what they need to be successful in kindergarten.

“All of that has sort of a long-term impact because if the child gets misdiagnosed in terms of special education, … We all know there is a strong connection with what happens in early experiences and how you are tracked early on and the outcome you will have later on in life.

“There is also a strong connection between what happens behaviorally in preschool in terms of how young children are being categorized or miscategorized with behavioral issues and how that leads to premature expulsion or suspension and that connects to a long legacy from the school-to-prison pipeline.”

Then why has Illinois placed a greater emphasis on early childhood education and health insurance than child poverty?

Lifson of Voices for Illinois Children has a theory on why the state appears to have done better in the areas of health insurance and early childhood education than poverty.

“It’s clear that while there has been progress in a number of areas, there is still work to do. I would say part of the reason that you see the improvement in terms of children who have health insurance and in terms of some of the education access to education, such as early childhood programs, it’s because the state made a deliberate effort to expand early childhood services, and it made a concerted effort to register children for health care. And so that’s been a success, and really, it’s an indicator that when the state makes a commitment to changing those measures positive things can happen.

“It’s important to continue to make those investments and to see what else we can do to reach those individuals to whom, for whatever reason, don’t have access to early childhood programs or, for whatever reasons, don’t have health insurance,’’ Lifson says.

State Rep. Greg Harris, a Chicago Democrat, is the chairman of the House’s Human Services Committee. He says he doesn’t believe the state has done enough to tackle child poverty or to boost early childhood services or health insurance numbers. He points to cuts made by the administration of Gov. Bruce Rauner as a factor

“We’ve seen growing poverty in the last number of years. We’ve seen increase in uptake in programs that serve families in poverty with food assistance, medical assistance, and other related services. And at the same time, we’ve seen the governor trying to reduce child care, try to limit the availability of food stamps, try to restrict enrollment in the Medicaid program, and it’s making it harder and harder for these families to meet the basic needs of their kids.”

His Republican counterpart, state Rep. Patty Bellock of Hinsdale, agrees with the need to do more about helping child poverty but says, “I think one of the major things we have to look at is the economy in Illinois. We need to create more jobs so more people can support their families. That’s crucial to bring children out of poverty.

Rowan of Voices, says, “If we’re talking also about helping families get out of poverty, that’s about creating economic opportunities for our families. Are there jobs for children’s parents? Are they jobs that pay a living wage? We know there’s been wage disparity so we want to make sure that we’re getting more families into living-wage jobs. So, does that require job training, additional education so we’re getting people access to full-time year-round positions that pay a living wage?”

Good government programs are a necessity, says Sujata of Chicago Foundation for Women. “We in philanthropy cannot fill the void that the government has put in place. We just don’t have the money, even collectively speaking, to step in and fill the voids when government doesn’t step up and provide … the safety nets that people require.”

Illinois Issues is in-depth reporting and analysis that takes you beyond the headlies to provide a deeper understanding of our state. Illinois Issues is produced by NPR Illinois in Springfield.

HomeWorks, a housing and schools campaign spearheaded by

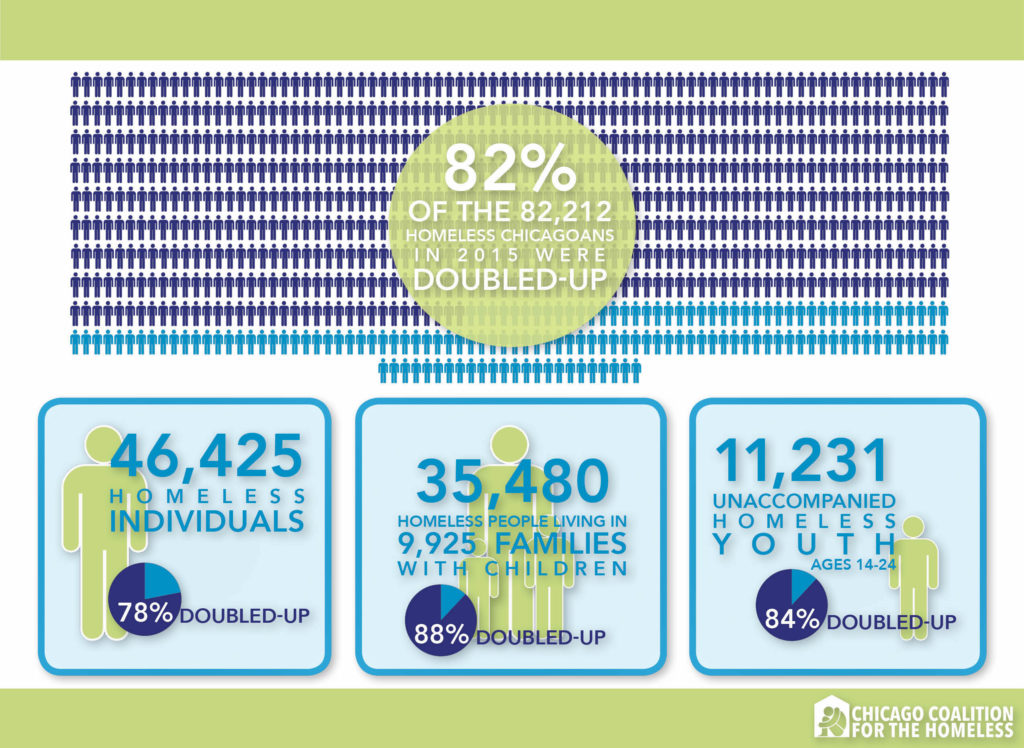

HomeWorks, a housing and schools campaign spearheaded by  Last year, HomeWorks worked with the mayor’s office and the Chicago City Council to enact a 4 percent surcharge on the house-sharing industry, making Chicago among the first municipalities to leverage a dedicated funding source for homelessness. CCH also pushed for the housing trust to dedicate new housing resources after CCH helped secure the release of escrowed funds owed the rental housing support program.

Last year, HomeWorks worked with the mayor’s office and the Chicago City Council to enact a 4 percent surcharge on the house-sharing industry, making Chicago among the first municipalities to leverage a dedicated funding source for homelessness. CCH also pushed for the housing trust to dedicate new housing resources after CCH helped secure the release of escrowed funds owed the rental housing support program. They include families like Chrishauna Thompson’s. Her family became homeless after Chrishauna’s mother suffered a back injury, leaving her unable to work two caregiver jobs. Over the next four years, Chrishauna, 17, changed schools nine times as her family doubled-up with different relatives.

They include families like Chrishauna Thompson’s. Her family became homeless after Chrishauna’s mother suffered a back injury, leaving her unable to work two caregiver jobs. Over the next four years, Chrishauna, 17, changed schools nine times as her family doubled-up with different relatives.